July 16, 2024

Director Zach Meiners Survived Conversion Therapy, Then Made a Doc About It

Kilian Melloy READ TIME: 7 MIN.

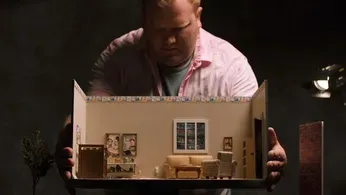

Zach Meiners has directed features ("Pivot Point," 2011; "I Am Potential," 2015), television (an episode of "Club Swim"), and a short film (the comedy "Icarus"). Now he turns his lens to the documentary format, and on himself, for the film "Conversion." Joining Meiners in sharing their stories of surviving of so-called "conversation therapy" are "Drag Race" star Dustin Rayburn, equality advocate Elena Joy Thurston, and longtime "conversion therapy" critic Wayne Besen, among others.

So-called "conversion therapy" has been denounced by reputable mental health professionals as a quack practice. Just on its face, it's hard to see "conversion therapy" as anything other than a pseudoscientific sham – latter-day snake oil that promises queer people they can somehow "convert" to cisgender heterosexuality through faith, exorcism, talk therapy, or some combination of all those things, plus a whole lot of willpower. It's an industry that critics say exploits the desperation of people who have been marginalized, excluded, bullied, and driven to self-hatred, all without delivering the results it promises.

Magical thinking and con-job quick fixes are as old as any other form of grift, and it's not surprising that the practice is embraced by people who have been indoctrinated into a corrosive self-hatred simply because they are queer. Acceptance, success, happiness, even an eternity in Heaven – the rewards are as nebulously slippery as the very notion of sexuality or gender identity being a "choice" or a "phase," or in any other way something other than innate, unchanging, and perfectly normal.

But it's hard to sell a fake cure for an invented pathology. To make an industry like so-called "conversion therapy" profitable, social, political, and religious fictions about queerness being "evil" or "disordered" must be championed, perpetrated, and actively mined for commercial opportunity. The downside of all this, of course, is that there is no "conversion," and this is not "therapy." Worse, while an industry such as this may tout claims of success, its true legacy is one of shattered souls and broken, betrayed people.

All doubt about that should have vanished when the leaders of prominent "ex-gay ministry" Exodus International gave up the jig and came clean, admitting that nobody was being "converted" from gay to straight and publicly apologizing for having pushed the notion that such a thing was possible. And yet, Meiners' new film notes, "conversion therapy" is thriving. It's simply found new brand names to go by, new ways to package its erroneous theories, and new customers to entice.

But that doesn't mean the fight is hopeless. Education, Meiners told EDGE, is the key to combatting "conversation therapy," and it was education he has sought to provide. EDGE heard more in a recent interview about the film.

EDGE: You put yourself into the film. Was that something you intended from the start, or did you realize there was no way to tell this story without telling your story as well?

Zach Meiners Initially I just wanted to make a PSA, but it became clear that one of the things that made this conversation different from other films was the fact that I had also been through [what I was talking about with the people I was interviewing]. We weren't having to explain a whole lot; we just understood each other.

In order for the audience to get that same sense, it became clear that I needed to be involved in the film. It took some convincing for me to do that. We did my interview multiple times, because it was hard for me to sit and release the director's side of my brain and allow me myself to be present.

EDGE: In the film, you talk about wearing rubber bands on your wrists and snapping them if you had erotic thoughts or feelings involving men. Did this crude form of aversion therapy change your feelings at all?

Zach Meiners Absolutely not. The rubber band was a small thing that showed this much bigger concept of, "This thing that is part of who I am, is the thing that is wrong about me."

I knew internally that my feelings were not changing. If anything, they were intensified. That started leading me to other forms of self-harm. That really affected me for many, many years. Those feelings, that shame, that self-harm was something that was taught to me. It's not something that I had in me innately as a kid.

EDGE: You talk in the doc about how your so-called "counselor" would ask you probing sexual questions and seemingly get turned on. Did you feel you were being exploited?

Zach Meiners It's something that was very uncomfortable for me, but when I talked to other people in the church about it, it was always, "You have to trust the process." Like, "You're the one who is the troubled child, so we're going to take his word over yours." When I wasn't believed I just kept quiet about it, but I did think that there was something wrong.

It took me many, many years to undo the damage. I stopped going to conversion therapy when I was 18. It wasn't until I was 24 that I knew I wanted to come out, but it took another couple years to get myself into a situation where I felt like I was able to safely come out.

Kilian Melloy serves as EDGE Media Network's Associate Arts Editor and Staff Contributor. His professional memberships include the National Lesbian & Gay Journalists Association, the Boston Online Film Critics Association, The Gay and Lesbian Entertainment Critics Association, and the Boston Theater Critics Association's Elliot Norton Awards Committee.